Blog Article: Reflections on Ghana (successes, impact and white saviourism)

By Ben Hall

Seva, Ghana

From 2021 to 2022 I was volunteer teaching in Ghana, on a very small island called Seva with a population of around 300. I had gone through a well-established and reputable charity named Project Trust[i].

During my time in Ghana I met many interesting people and created strong bonds with the members of my community in the island. I learnt and was aided in cooking the food and picking up the local language. We participated in an exchange of ideas – it was interesting for the kids to get to know us and hear about our experiences just as it was for us to understand more about their culture.

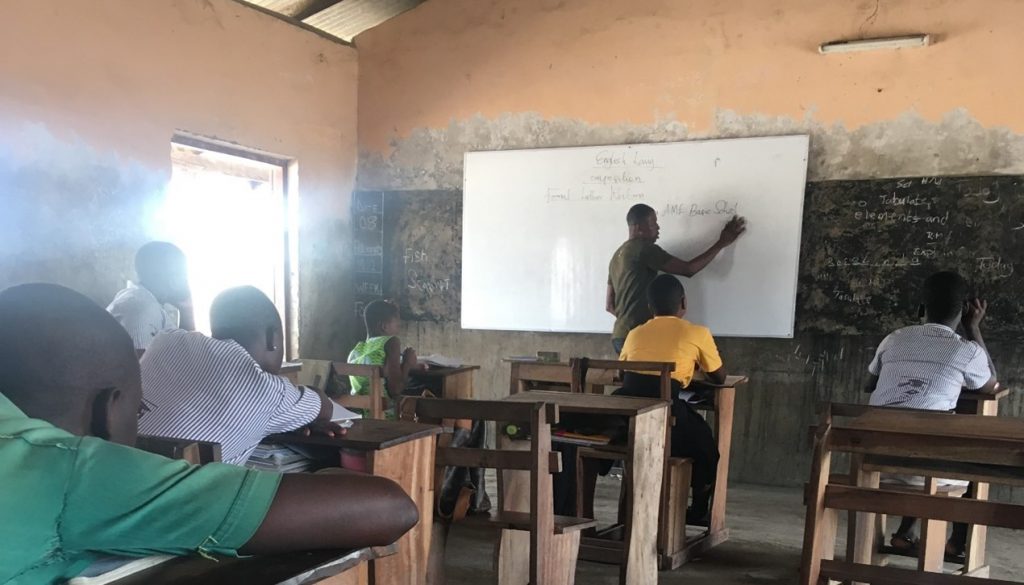

The English-speaking skills of the children greatly improved, which would benefit them in finding higher paying jobs in Accra, the capital. Also teching other subjects such as Maths, Science, Art, RME and Geography and consistently put effort into the teaching, creating thoughtfully crafted lessons. We weren’t taking jobs away from Ghanaian teachers as even while we were there the headmaster and school faculty constantly stressed that they were trying, and often failing, to get more staff. Volunteering for an extended period of time so there was room to develop our teaching skills and get to know the children on a personal level, which aided in their education.

However, we still left. A large criticism of Western Volunteering in developing nations is the length of time that Volunteers spend at their projects. Its common to do a few weeks building a school or playing with orphaned kids, and then leaving to travel, only having understood the surface level of the community and, in these cases, not actually helping them whatsoever. In one example, volunteers building a library were so bad at it that the African builders aiding them dismantled their work overnight and redid it, without the volunteers even knowing[ii]. This wasn’t aiding the orphanage – it was so the charity could make money and so that the volunteers could feel good. It wasn’t an isolated occurrence.

I was teaching for almost 10 months. However, I had to take time at the start to improve my teaching skills and learn how to navigate the school I was in. All the volunteers had was a quick training course, with a mock 10 and 20 minute lesson and advice on cultural awareness. This is better than a lot of other volunteering charities, but its still not enough. We all agreed about that. If a school in Ghana is going to have a volunteering teacher, the ideal would be for them to be well-trained and have experience.

This ties into the fact that in many Ghanian public schools there are a lot of structural problems that we couldn’t hope to address. Some of the local teachers felt it normal to skip classes when they felt like it. Others, who were positioned in the school by the government, also had the same problem that we had.

The government can allocate Ghanaian teachers and take them away from a school whenever it feels like it. A teacher might find their groove in a school, only to be relocated to a completely different one. This is what happened to the headmaster at Seva, who had no desire to leave. Besides that, the exams are not created to an adequate standard, including questions that weren’t on the curriculum and blatant spelling errors. In the end, we felt like we had made significant progress with the kids but these couldn’t be reflected in the results, which is frustrating for the students that put so much effort into revising what we taught them.

The second issue is perpetuating narratives of how African countries relate to the west. Many of the kids told us what they thought of the UK and America, about how rich everybody was and how much they wanted to visit. Random Ghanaians would come up to us and ask for handouts, or for us to take them back on the plane, or get them a visa. Some of them jokingly referred to having us smuggle them in our suitcases. Why is it that a lot of Ghanaians, and many Africans, constantly view the West as superior? While colonialism is no longer present physically, imperialist mindsets are still alive. Its easy to see why Ghanaians might have rose-tinted glasses about the west. A lot of their media consumed is from America and when they might see a foreign tourist, they are usually well-off and secure.

The majority of the volunteers that went and continue to go abroad are wealthier and predominantly white. The exchange rate is also extremely unbalanced, to our advantage. We could get a satisfying breakfast for the equivalent of 10p in the UK. The narrative becomes one of the rich white saviour, coming to ‘save’ helpless Africans from poverty. While the west may be more wealthy than sub-Saharan Africa on the whole, the problem is that Westernisation is seen as the only way to progress, and many Africans believe that the only way for a better life is leaving their country and moving to Europe or North America. These ideas aren’t often challenged by western people.

While many Africans think that Europe and North America are lands of endless wealth westerners also fall into the trap of viewing Africa as a monolith. There are lots of videos on YouTube where an interviewer will ask people from a western country what they think of Africa and the answers will be ‘poor’ or ‘poverty’ [iii]. Many do not realise the vast amount of progress that a lot of these countries have achieved. A lot of people I’ve talked to are surprised to hear that Accra – the capital – is a metropolitan, urban city with skyscrapers, malls and fancy restaurants. There are well-respected universities, cinemas and museums all over Ghana.

Just like the UK, there are places of extreme wealth and places of extreme poverty. However, it makes sense that a lot of people think this way as a lot of the stories returning volunteers relate will be about the poor living conditions in the rural village that they stayed in, and how challenging yet rewarding it was to help them.

But a single narrative is harmful. One kid named Clementine came up to us one day and told us that sometimes she hated God because he had made her Black. To her, being Black was a curse and a disadvantage, something which meant that it was harder to live a successful and secure life. If she was white and western, things would be easier for her. This is an implicit narrative that is perpetuated, whether we mean to or not. The kids, when we asked them to draw themselves, drew themselves as white. That was what they saw when they watched TV. Aside from Nollywood pictures (Nigerian live-action films) every piece of media featured white characters. And this can be worse when volunteers act like they’re superheroes, generously benefitting a black community when they introduce them to pizza for the first time.

Another side is photos, the way volunteers present their experiences online. I was aware of the white saviour trap before going, of the classic image of a white volunteer surrounded by black children that they probably barely know, suggesting altruism. It’s another thing that perpetuates the impoverished Africa / wealthy west narrative. So I decided not to use social media while I was there. However, on coming back I had made real connections with many of the kids, teachers and residents in my village.

I had photos and I felt that since they were those I knew, it would be nice to share those experiences on Instagram. There were pictures of me with Ghanaian kids, but they were ones I had known for 10 months. They had real meaning to me. But whenever I thought about these pictures afterwards, there was a dissonance between what I saw them to be, and how they looked. Really, all these images perpetuate a white saviour narrative when they’re without context. They look the same and they make others think the same thing – that you met all these African kids and gave them the benefits of your Western upbringing. It doesn’t matter what the truth is if you don’t give context. It’s the images that speak.

So why don’t privileged Ghanaians volunteer themselves instead? It isn’t for a lack of desire. In a chance encounter I met a politician from Accra, whose son was interested in helping out in a school in a rural area. She asked me to pass on the details of the charity I had gone with. But this was a Scottish charity and it would be very hard for a Ghanaian to travel all the way to Scotland to train and be assessed like we were. This was a charity made for western young adults to volunteer, not a Ghanaian.

So the question is, why is it easier for somebody from the UK to volunteer in a Ghanaian school than it is for an actual Ghanaian? There is a power imbalance there, that western people can still use to gain opportunities that others can’t. The Ghanaian government unequivocally holds blame, as there is not enough done to equip schools with the resources and people that they really need. Corruption is a real issue and a lot of the time its hard to tell where the money is actually going. Very little trickled down to Seva, despite the need for it. So, in place, overseas volunteering keeps being accepted gratefully.

“Whilst I strongly believe in the impact that overseas volunteers can make in a communities, to see real and sustainable change the members of that community itself must be leading on projects.” – David Coles, Kickstart Ghana[iv]

Overall, I believe our volunteering was valuable and necessary but in an ideal scenario there wouldn’t be a need for us. The goal should always be for an end to reliance on volunteering, not letting the government kick back and relax with a guaranteed group of overseas volunteers every year. It’s a paradox, because the need is often there yet when we fill those gaps the people in power feel that that they don’t need to do anything more. There’s no easy answer, but I feel that the focus should always be in enabling members of the community to find solutions themselves.

One example is Kickstart Ghana, a joint UK and Ghanaian NGO which started out with a focus on overseas volunteering before shifting to Ghanaian volunteering as well. Like with our charity, people from overseas are screened beforehand – which I believe should be the norm. In their manifesto, they highlight the importance of structural change and creating frameworks for improvement. While we were at our project we wanted to help benefit structural change, like creating a library, but it’s hard to know our long-term impact.

I’m so thankful to have gone, and I know I and many of the people in Seva got a lot out of our being there. For me, it was wonderful and everything I wanted – to get to know people of another culture, to teach and to learn about the individuals in my class and how best to get through to them. But looking back, I see a structure and pattern of the relation between sub-Saharan Africa and the west and the colonial narratives that are still around today. I know the most benefit would be from the ground up, from empowering Ghanaians in these rural areas to create their own change, and for the government to give them the resources to do so.

[i] What is Project Trust? (2023). Retrieved from Project Trust: https://projecttrust.org.uk/about-project-trust/what-is-project-trust/

[ii] Biddle, P. (2014). The problem with Little White Girls, Boys and Voluntourism. Retrieved from Huffpost: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/little-white-girls-voluntourism_b_4834574

[iii] (Asking Europeans What They Think of Africa) https://youtu.be/ChyPpnQaBs0

(Europeans React: Which AFRICAN Country Would You Like To LIVE In? **Or Relocate To?** 2.36) https://youtu.be/DwRcrfgbux8

(AFRICAN DON’T HAVE WATER/ AFRICANS ARE POOR/African stereotypes WHAT COUNTRY IN AFRICA YOU ARE FROM? (Americans)) https://youtu.be/f_EQ7WnYtco

[iv] Coles, D. (2015). Volunteerism in Ghana: Alive and Well. Retrieved from LSE: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/africaatlse/2015/11/03/volunteerism-in-ghana-alive-and-well/